30. Coolah (NSW)

19 July 2018

Brian was never keen to discuss his early years. What he did disclose was depressing enough but not as grim as his father’s anecdotes, which I suspected were closer to reality. They were all about a mother who had little time for their five children, especially the sickly little boy who was her second-born. It was a rejection she reinforced throughout his life and while he could have given in to bitterness, his stubborn resilience preferred to focus on all the good people in his world, especially his beloved grandma and the relatives and neighbours who stepped in when needed.

When Brian was born in 1952 his father was working as a railway ganger in the small country town of Coolah, 370km north-west of Sydney. Coolah was then a typical terminal station at the end of the Craboon sub-branch line, and a major service town for the surrounding Warrumbungle Shire. Today, as with too many drought blighted regions in the west of the state, it struggles to survive at all.

Ted moved his family back to Sydney soon afterwards and though the marriage was already toxic, it produced three more children, a girl and two boys. When his parents split Brian was nine and took on responsibilities not just for his younger siblings, but also for a dad struggling through bouts of depression and financial hardship, and alcoholism. This was exacerbated when Elva and her new husband would reappear to demand visitation with the children, but insist “We can only take three of them in the car”. This never included Brian and although he would tell me this matter-of-factly, shrugging that he learned not to care, it was clear the dagger never lost its edge. A chance meeting at a shopping centre when he was about 30, where she recognised his younger brother but just stared blankly at Brian, must have driven it deeper.

Sometime after that he visited his birthplace while on a lads’ weekend to nearby Dunedoo, and by that time Coolah’s railway line had been closed and local industry was in decline. But I assume he was there in the milder months and that general conditions were not so dire, as he described its “busy” main street and the beauty of the surrounding countryside. The Coolah that Ken and I experienced was almost barren of life, either in the paddocks or on the streets, and though cold winter winds and an ongoing drought would not enhance any landscape, there was little sign that the town had a commercial future.

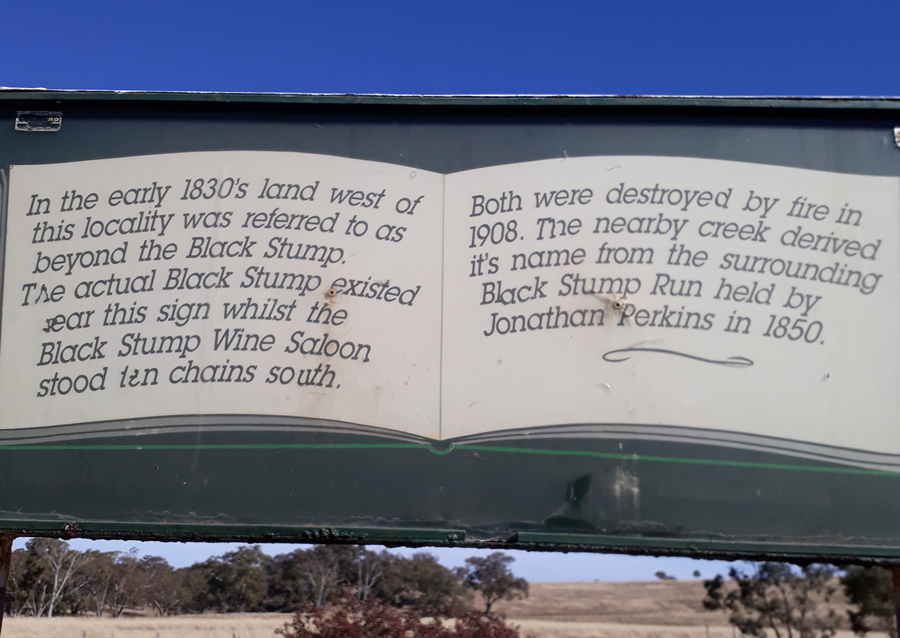

Coolah is one of several contested locations of the original ‘black stump’, the fabled point past which Australian civilisation ends. The town’s claim is feasible: history records that when Governor Darling defined settlement limits in 1829, he nominated a boundary line that passed along the approximate site of Black Stump Run, just north-west of present-day Coolah. As the local Gamilaraay people called the area Weetalibah-Wallangun – “place where the fire went out and left a black stump” – that was good enough for modern-day Coolah and the Black Stump Rest Area was erected a few kilometres to the north, on Black Stump Way. It’s here, smack in the hollow of that legendary stump (or at least in its replacement), that some of Brian’s ashes get to rest, close to where his life began.

It was a life that did get better and he was adamant at the end that he was happy (“I’m going out feeling a lot more loved than when I came into it”). He finally had the strong family life he craved and though his estranged sister Jenny died before they could reconcile, and he had long given up on the older brother he hadn’t seen in 30+ years, he still had contact with his two younger brothers and also got to enjoy some precious approval from his father. His relationship with Ted was awkward but Brian could see through that to a loyal heart that truly loved his son, and before he died Ted confirmed this. Through tears he apologised for not saying it sooner and begged Brian not to waste time wondering why his mother never had.

That scar had been flipped open a few years before when she called him, her breezy “Brian, it’s Mum” ignoring decades of silence. His reaction was carefully polite, with nothing in it of the shock on his face, but the consequent asthma attack and sleeplessness were inevitable. She’d rung to let him know about Jenny and followed it up with a copy of the death notice, her return address on the envelope. Bizarrely, she seemed to think a lifetime of neglect could be erased if she just didn’t mention it. Her indifference to his feelings was torment but though he never called her back and rarely mentioned it again, he would not hate her: “Not for her; for me.” I couldn’t understand but it was his choice… and in the end, I think, his victory.